Shy sweetheart fingers eagerly slipped into the honey jar under golden hour glow. Dirtied soles dragging across lily-white floors. Entwined limbs setting aflame with joy. Candle wax drips onto skin. Scrupulous sweetness in quasi-orans pose, anointed by treacly little teardrops in place of holy water. Blanketed body heat, warm breaths in the throes of love. Panicked realizations: the weight of guilt transposed over the most delicate of desires, longing to be cleansed of blight. Abject makeshift confessional booth whispers. Half-sung lullaby preceding light-as-a-feather kisses goodbye. The price of sweetness: a mind in upheaval, eschewing wreckage of regret humming Hildegard von Bingen.

White florals occupy a peculiar space in folklore. At first glance they seem to be flowers of contradiction, embodying innocence and purity while simultaneously notorious for their heady, seductive powers; but these are two sides of the same coin.

Orange blossoms have stood as a token for purity, chastity, and innocence all throughout history, but they also act as a powerful symbol for fertility, as they could bear not only just flowers, but bountiful fruit eager to be harvested as well. In China, a long-standing tradition of tucking orange blossoms into a bride's trousseau remains actively practiced. Jasmine oil has long been favored as an aphrodisiac in India, and in religious ceremonies of the region it additionally serves as an emblem of purity and forgiveness. Bridal rooms are decorated with tuberose, and after wedding ceremonies, a bedroom filled with jasmine and tuberose awaits newlywed couples. Tuberose remains a popular choice for bridal bouquets for its associations with peace and purity, but its seductively saccharine roots run deep. At the tail end of the Italian middle ages, tuberose was brought from Mexico to Europe, and young women—assumed virgins—were prohibited from roaming through gardens hosting tuberose, as the scent of the flowers was considered so erotic that it would be dangerous for any "pure maiden" to inhale it, potentially causing them to have unchaste thoughts and desires.

From the house: "The double nature of any human being: longing to perfection, innocence, absence of mistake, to a place uncontaminated by sin from one side, and the inevitable fallibility and impossibility of amending mistakes. The combination of white florals and animalic facets represents this dichotomy, as an invitation to accept both idealism and imperfection as a very specific human feature."

On one hand rests a pungent array of spices and secretions—castoreum, ambergris, cumin, coriander, cinnamon—and on the other a pallid bouquet of blooms—jasmine, orange blossom, magnolia, ylang-ylang. Opening with bright citric sparks which quickly dissipate in favor of thick resins and warm spices, Lost in Heaven imitates the rush of desire. The animalic notes are expertly blended, melting together in a delightfully dirty carmagnole. Alongside the sweetness of candied corollas, musk coupled with ambergris' signature sea-breeze saltiness gives an impression of hot flesh. A civet note becomes prominent as the scent progresses, turning up the heat even more. Honeycomb hexagons are squeezed and sapped of their nectar over a bed of opoponax, resulting in a palatable waxiness which knows its place, enhanced by the starchy dryness of orris root, all while honey drips onto quivering lips. Oily cumin and animalic ambergris tease white flowers into submission in a seamless meshing of floral-moral contrasts, reaping the results of a slow-burn jasmine enfleurage. Indoles walk the line dividing the abject and the prurient as a demure, pastel creaminess rears its head.

Lost in Heaven is a dense maze in which the compact walls separating right from wrong crumble at the touch. A fellow fan of the scent described it as "full-bodied," which I couldn't agree more with, unable to resist from viewing it as a double entendre denoting the voluptuous qualities of the fragrance. Honey coats the entire concoction, thick and syrupy with the iconic Bianchi DNA present. The cumin is sour and spicy, painting a portrait of sweaty sheets in all their piquant post-coital glory. Puffs of powdery mimosa provide an airy softness in complementary contrast to the heaviness of honeyed erotic filth. The gentle but self-assured nature of white flowers slowly begins to shine as pale petals unfurl from the heart of the fragrance, with orange blossom and jasmine being most prominent on my skin. Creamy sandalwood lies at the base, caressed by a cold lily-like accord peering from the sensual smog every so often, a welcomed surprise in the last huffs and pants of the drydown.

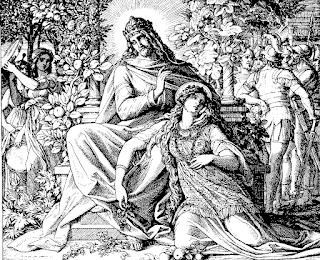

Lilies are mentioned over a dozen times throughout the Bible—eight of these instances appear in the Song of Songs, a dialogue between a two unmarried lovers brimming with shared erotic passion indistinguishable from religious ecstasy. While the loss of innocence in the story of the Garden of Eden is a tragedy with grave ramifications, the transformative sensuality present in the Song of Songs is nothing short of revered, recognizing that love is God and God is love in the following translations by Ariel and Chana Bloch: "Kiss me, make me drunk with your kisses! Your sweet loving is better than wine ... You are fragrant, you are myrrh and aloes ... My king lay down beside me and my fragrance wakened the night ... His cheeks a bed of spices, a treasure of precious scents, his lips red lilies wet with myrrh. I am the rose of Sharon, the wild lily of the valleys. Like a lily in a field of thistles, such is my love ... My beloved is mine and I am his. He feasts in a field of lilies ... Your belly is a mound of wheat edged with lilies." Lilies become synonymous with a holy union of flesh and spirit regardless of marital status in the Song of Songs, and to this day it is believed that the tomb of the Virgin Mary was gracefully adorned with them.

The Hebrew word "dodim" is used six times in the Song and three outside of it, with the utterances outside of the Song explicitly referring to intercourse, kisses, and sensual caresses; yet in the Song it has long been commonly translated as simply "love." The two lovers are introduced as consummated yet unmarried in the original Hebrew, and the real life Solomon himself had hundreds of concubines. The Song was subjected to intense scrutiny and barred from canonization until the second century, at last accepted only once it became popular to view the Song as a metaphor of one's relationship with God, instead of a sensual poem. Despite erotophobic stoics' attempts at shrouding the eros in the Song with intentional mistranslations and obtuse allegories, the overt lust of the original Hebrew texts have been brought further to light by contemporary scholars in recent decades. Even before such efforts, the frigidly translated versions could never mute the ardor still practically dripping off the pages of any diluted King James Version.

White flowers continue to be a powerful badge of purity, not despite the now-repressed eroticism of the Bible but in part because of it. However frequently misguided, attempts at forming spiritual allegories are not entirely in vain. The eroticism in Song of Songs does not negate the holiness of its love but rather reinforce it, leaving plenty of room for allegories on soul unions with both God and a lover, and space for lilies to flourish as concurrently pure and sensual, for all who live in love live in God and God lives in them. Beyond vulgar interpretations of the word based on the myth of being physically sullied, the Christian conception of purity remains a largely unattainable metaphysical state to continuously strive for against all odds; but in an alternate sense of the word, purity permeates all actions born out of love and grace. To be able to even attempt to live and love in the name of goodness remains a holy gift regardless of formalities and external factors.

Simone Weil is as relevant as ever: "To reproach mystics with loving God by means of the faculty of sexual love is as though one were to reproach a painter with making pictures by means of colours composed of material substances. We haven't anything else with which to love. One might just as well, moreover, address the same reproach to a man who loves a woman. The whole Freudian doctrine is saturated with the very prejudice which he makes it his mission to combat, namely, that everything that is sexual is base." [...] "Purity is the ability to contemplate defilement. Extreme purity is able to contemplate both the pure and the impure; impurity is able to do neither: the pure frightens it, the impure absorbs it. (It requires to have a mixture.)"

To live is to contradict and see-saw, and acceptance of this is not embracing any semblance of "impurity," but rather relishing life itself as a dialectical experience, learning through action and coming to terms with not only ourselves, but morality, love, death, sensuality, resentment, ecstasy, and transgression.

My dear friend Parish recently came to me to gush about some of Leibniz's metaphysics and the idea of completeness of human essence, which soothed my soul, and I can't help but find it pertinent as well:

"Human beings, being the complete and perfect notion of individual substance, contain within themselves the perfect necessity of their being. This means that every particularity of each individual was not only necessary, but perfectly necessary. In accordance with being in the best of all possible worlds due to God's omnibenevolence, you, I, and every person are exactly perfect in our essences as the agents to actualize that world. In complete knowledge of your full glory, of everything you are, everything you've done, and everything you will ever do, God chose you to become actualized out of an infinite array of beings infinitesimally different from you. Down to the smallest particularities about yourself, to the level of the exact arrangement of molecules in your body, the number of hairs on your head, every action you have taken and everything you will ever do, all of it is absolutely perfect and necessary to the end of the maximum amount of goodness in the universe.

Perhaps a difficult notion to take at face value, especially in light of Spinoza’s improved metaphysics and whatever distaste we might retain for optimistic philosophy under our current social situation, but it's lovely to think about, isn't it? Out of every possible you, or variant of who you could have been, you exist exactly as you are because everything about you is directed at the end of perfect goodness.

I like to imagine Sartre and all the other metaphysics-bare existentialists reading that and frothing at the mouth."

The achievement of love and kindness akin to God's nature is so glorious precisely because it is a prize for which we must fight with our animal nature. Striving for purity of heart is significant not because it is a weak, futile imitation of God's purity, but because, despite how prone we are to selfishness, we may demonstrate a will power to overcome it that is far more divine than isolated "purity" itself. The significance lies in the fight, not the mere outcome. One chooses to fight for ideals, never ontologically imprinted on one's soul. Purity is a process of becoming before being.

"Where is the divinity in being in an inherent state of perfection like a pawn on God’s chessboard rather than being this sickly stupid little creature that is so willing to tear itself to shreds in the name of love?"

*Translations of The Song of Songs which largely skirt around the overt eroticism are entirely not without merit, with beautiful moments from both the KJV and NASB being plentiful. From the latter: "Sustain me with apples, because I am lovesick. His left hand is under my head, and his right hand embraces me," and from the former, "Thy lips, O my spouse, drop as the honeycomb: honey and milk are under thy tongue; and the smell of thy garments is like the smell of Lebanon."